FIGURE EIGHTS

Now available as an Audio Story read by Jill Eikenberry

Back in our jackpot years, when we were able to own and care for horses, I had a bit of a love affair with a dark chestnut quarter horse named Tico. Quarter horses are bred to work cattle. Some are trained for cutting, some for racing and some, like Tico, for cow reining, which is the art of moving and controlling a herd of cows. On the day I bought him, in the high desert near Prescott, Arizona, his then-owner boasted that if Tico had any more cow in him, he’d be a cow. He was also a pleasure to be with on the trail, and I spent some of my finest hours riding him in the redwood forests and along the streams and beaches of Andrew Molera State Park, which bordered our land.

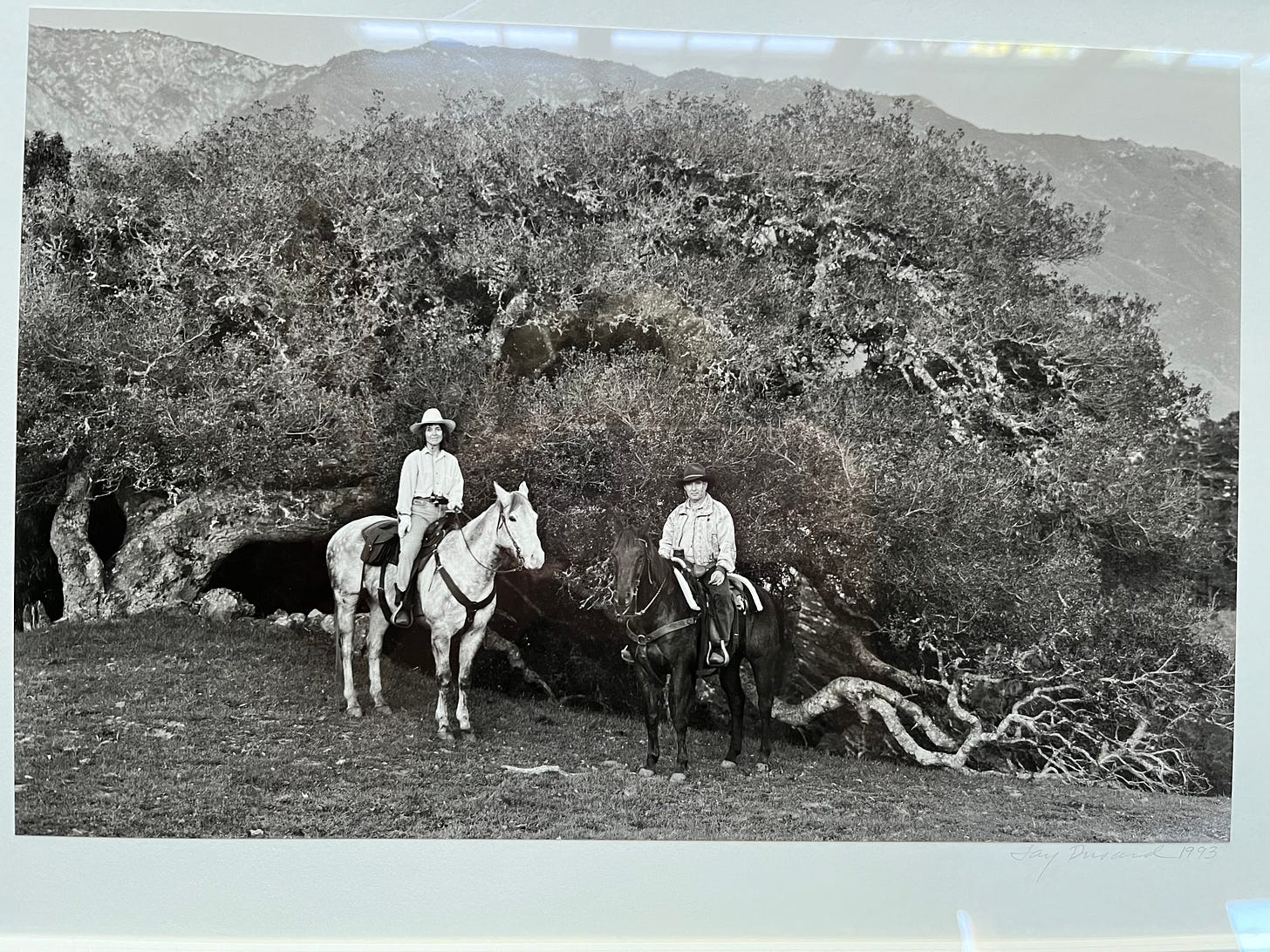

We had a cowboy on staff in those days. His name was Dave, and he was a genius at buying horses with other people’s money. We had more horses than we had asses to put on them. But Dave taught us everything we know about horses, cowboys, boots and rodeos. We once competed in the Santa Barbara Rodeo in an event called team penning, which is a timed event that involves moving cows around an arena in ways more complicated than I have time to explain right now. But it was thrilling, I can tell you that.

Dave also schooled our horses and kept them healthy and tuned. We had a house on the top of Pfeiffer Ridge in Big Sur, California and another twenty acres down the road where we kept the horses. There were stalls, pastures to graze, and an exercise arena in the middle of a big open field that looked to the ocean on one side and over to the Big Sur mountains on the other.

We would always start the day by cleaning our horses’ hooves, which is a great lesson in learning how small you are. You hold a hoof pick in your right hand and gently lean your weight against the horse’s left shoulder, so that he shifts his weight a bit to the other side. Then you reach down with your left hand and take a light hold of his lower front leg, at which point the horse, who wants the hoof to be cleaned, lifts his leg for you, and you go about your business. You could look at it as a kind of foreplay.

After putting on his saddle and bridle, I’d lead him over to the arena, which was a large rectangle bordered by railroad ties all around. I’d clip one end of a long rope onto his bridle and start an exercise called lunging, which was simply getting him going in a circle, with me -- holding the other end of the rope -- in the middle. He was trained to respond to a couple of vocal commands -- two clicks with your tongue to have him go into a trot; two kisses to put him into a canter.

We’d start easily – three or four circles in a slow trot in one direction; then the same going the other way around. Turning was the hardest part, but once we had done it ten or twenty times, we got good at it. He’d be going around in his trot and I’d say whoa. That’s right – whoa – just like in the movies. I’d say whoa and he’d execute an almost imperceptible four-footed slide forward -- he slid maybe three inches. And then he’d back up an inch and pose, waiting for the next cue. He knew how good he looked when he did this. Then I’d pull him gently toward me with the rope, circle around behind him and double-click him into a trot going the other way around. He’d trot in a wide circle, steady and easy. And breathtakingly beautiful.

After a while of that, I put him into a canter, which he was eager for. Two little kiss sounds, and he stretched his legs out into a lope, which is cowboy for a slow canter. Going in a right circle, he naturally fell into a right lead, which means his right front leg led the rest of him around the circle. If he did a left circle, he would naturally go into a left lead. And if he did the shift on the fly, that’s figure eights.

When his coat started to shine, I clicked him down to a trot for a couple of circles and then gave him a whoa. I walked him around the perimeter of the arena, then I unhooked the lunge rope, tightened his girth strap and got up on his back. We slow-walked around the perimeter, this time connected to each other. Then we executed the same circles as before, trotting, then loping; to the right and to the left, getting the feel of each other; him getting used to the feel of me on his back. Then I walked him to the approximate center of the arena and faced him due west, toward the ocean.

Imagine, if you will, the figure eight; then lay it on its side. The point where the circles meet is what I’ll call the top of the circle. From there you can start a circle to the right or one to the left.

A bit about steering, which is one of the things that make western riding different from its English cousin -- the way one holds and uses the reins. English riding is about having control over your horse, whereas Western riding is more about making some well-practiced suggestions.

An English rider holds one rein in each hand; if he wants the horse to turn to the right, he pulls back on the right rein, pulling the horse’s head in that direction. A western rider holds both reins in one hand, loosely, just above the withers, which is where the horse’s neck meets his shoulders. If the rider wants to turn to the right, he moves his hand, which is holding both reins, an inch or two to the right. The horse feels the left rein touch his neck and moves to the right. Horses move away from pressure – even the lightest pressure.

So, we’re standing at the top of the circle – remember our sideways figure eight? We’re in the middle, where the two circles touch. I give Tico a double click, move my reins to the right, nudge him a little with my butt, and we’re into a lovely trot, moving clockwise around the circle. After a few of those, I give him a double-kiss and we stretch out into a lazy lope with Tico on a right lead in the same clockwise direction. After a while, I’ll stop at the top of the circle and then repeat that whole process on his left lead – going counter-clockwise.

Now we’re warmed up. It’s time for figure eights and flying lead changes. The whole idea is not to let him – or me – get into a set pattern. Sometimes I’ll change the lead after three circles; the next time after one. Sometimes, I’ll keep him on a left lead for six or seven circles, and as we approach the top of the circle again, I can feel him wondering if it’s time to change.

“Uh, uh, big boy, I’ll tell you when.” And he shakes his head in disbelief and stays on his left lead.

One morning, Cowboy Dave was around when I was going through this warm-up process, and he gave me a tip.

“Get into a right circle, and when you’re ready to make a change, don’t move your hands at all. Just hold the reins dead-center, and turn your eyes to the left.”

“Just my eyes?”

“Yep.”

It worked! I immediately tried it to the right. I moved nothing. I swear. No pressure from my leg; no little wiggle in my butt; the reins were suspended dead-center over the withers. Just my eyes. And Tico effortlessly executed that truly balletic move, changing his legs in mid-air from left lead to right. And then he gave me another shake of his head, telling me that he knew how impressed I was and what a naive fool I am. He was in a good mood.

Then Dave said, “Now just think it. Don’t move your eyes. Don’t move anything. Just sit your horse, and think which way you want him to go.” And then he walked over to his truck and drove away.

We made circles for I don’t know how long, communicating simply through desire. To the left, to the right; changing, not changing; Tico knew exactly what was on my mind.

Then my mind let go. Of its own accord, it just let go -- of thoughts, of desires. And the circles continued – to the right and to the left – and I cannot for the life of me tell you who was making those decisions. And Tico shook his head as if to say, “What took you so long?”

This was all many years ago. We’ve sold our Big Sur property, part of which we used to finance our house in Italy. Dave moved the horses south to a ranch he’d be working on in the Santa Ynez area. Tico, who had been retired for a while by arthritis in his leg, went to work again with Dave, who used him as a school horse for children. Dave says he’s never seen him happier.

I had no idea-the horse years. The way you tell stories within a story . . . With all their tender meanings.

What a lovely memory. Being in partnership with a horse is a magical experience.